In Christianity, Trinity is the doctrine that God is one being who exists, simultaneously and eternally, as a mutual indwelling of three persons (not to be confused by "person"): the Father, the Son (incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth), and the Holy Spirit. Since the 4th century, in both Eastern and Western Christianity, this doctrine has been stated as "three persons in one God," all three of whom, as distinct and co-eternal persons, are of one indivisible Divine essence, a simple being. The doctrine also teaches that the Son Himself has two distinct natures, one fully divine and the other fully human. Supporting the doctrine of the Trinity is known as Trinitarianism. The majority of Christians are Trinitarian, and regard belief in the Trinity as a test of Christian orthodoxy.

Opposing nontrinitarian positions held by some groups include Binitarianism (two deities/persons/aspects), Unitarianism (one deity/person/aspect), the Godhead (Latter Day Saints) (three separate beings) and Modalism (Oneness).

Historically, the doctrine of Trinitarianism is of particular importance. The conflict with Arianism, as well as other competing theological concepts during the fourth century, became the first major doctrinal confrontation in Church history. It had a particularly lasting effect within the Western Roman Empire where the Germanic Arians and Nicene Christians formed a segregated social order.

Contents

|

Etymology

The word "Trinity"— "Tri-unity"— comes from "Trinitas," a Latin abstract noun that means "three-ness," "the property of occurring three at once" or "three are one." The Greek term used for the Christian Trinity, "Τριάς" ("Trias," gen. "Triados") means "a set of three" or "the number three,"[1] and has given the English word triad.

The doctrine of the Trinity is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, argued in debate and treatises.[2] The concept was expressed in early writings from the beginning of the second century forward.

The first recorded use of the word "Trinity" in Christian theology was in about AD 180 by Theophilus of Antioch who used it, however, to refer to a "triad" of three days: the first three days of Creation, which he then compared to "God, his Word, and his Wisdom."[3][4] He compared the fourth day to humanity, as a needy recipient of the first three, forming a tetrad. The creations in the fourth, fifth, and sixth days are said to intimate both righteous and unrighteous members of humanity. God rested in the seventh day, the Sabbath.

Tertullian, a Latin theologian who wrote in the early third century, is credited with using the words "Trinity" and "person" to explain that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were "one in essence— not one in Person."[5]

About a century later, in AD 325, the Council of Nicea established the doctrine of the Trinity as orthodoxy and adopted the Nicene Creed that described Christ as "God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance (homoousios) with the Father."

The Holy Trinity

Trinity in Scripture

Neither of the words "Trinity" nor "Triunity" appear in the Old Testament or New Testament. Various passages from both have been cited as supporting this doctrine, while other passages are cited as opposing it.

Summarizing the role of Scripture

Many passages from the Old Testament have been cited as supporting the Trinity, and the Old Testament depicts God as the father of Israel and refers to (possibly metaphorical) divine figures such as Word, Spirit, and Wisdom. Some biblical scholars have said that "it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions with later Trinitarian doctrine."[6] According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, a few of the Fathers "found what would seem to be the sounder view" that "no distinct intimation of the doctrine was given under the Old Covenant." [7][8] "Some of these, however, claimed that a knowledge of the mystery was granted to the Prophets and saints of the Old Dispensation.[9] The matter seems to be correctly summed up by Epiphanius, when he says: "The One Godhead is above all declared by Moses, and the twofold personality (of Father and Son) is strenuously asserted by the Prophets. The Trinity is made known by the Gospel".[10][8]

The New Testament also does not use the word "Τριάς" (Trinity), nor explicitly teach it.[11] The Trinity article in Encyclopedia Britannica states: "Neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament, nor did Jesus and his followers intend to contradict the Shema in the Old Testament: "Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord" (Deuteronomy 6:4)."[12]Encyclopedia of Religion, for example, argues that "God the Father is source of all that is (Pantokrator) and also the father of Jesus Christ. Early liturgical and creedal formulas speak of God as "Father of our Lord Jesus Christ"; praise is to be rendered to God through Christ (see opening greeting in Paul and deutero-Paul). There are other binitarian texts (e.g., Romans 4:24; Romans 8:11; 2 Corinthians 4:14; Colossians 2:12; 1 Timothy 2:5–6; 1 Timothy 6:13; 2 Timothy 4:1), and a few triadic texts (the strongest are 2 Corinthians 13:14 and Matthew 28:19)."[6]

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, while Trinity does not explicitly appear in the New Testament, its basis is established by the New Testament: The coming of Jesus Christ and the presumed presence and power of God among them had implications for the early Christians. "The Holy Spirit, whose coming was connected with the celebration of the Pentecost. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were associated in such New Testament passages as the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19); and in the apostolic benediction: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all" (2 Corinthians 13:14)."[12] The Great Commission reflects the baptismal practice at Matthew's time (or later if this line is interpolated, according to The Oxford Companion of the Bible). Aside from this verse, although "Matthew records a special connection between God the Father and Jesus the Son (e.g., Matthew 11:27), but he falls short of claiming that Jesus is equal with God (cf. 24:36)."[13]

According to the The Oxford Companion of the Bible, 2 Corinthians 13:14 is the earliest evidence for a tripartite formula. The Oxford Companion of the Bible states that it is possible that this three-part formula was later added to the text as it was copied. However, there is support for the authenticity of the passage since its phrasing "is much closer to Paul's understandings of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit than to a more fully developed concept of the Trinity. Jesus, referred to not as Son but as Lord and Christ, is mentioned first and is connected with the central Pauline theme of grace. God is referred to as a source of love, not as father, and the Spirit promotes sharing within community."[13]

The Gospel of John does suggest the equality and unity of Father and Son. ("I and the Father are one" John 10:30). This Gospel starts with "the affirmation that in the beginning Jesus as Word "was with God and ...was God" (John 1:1) and ends (chap. 21 is more likely a later addition)[citation needed] with Thomas's confession of faith to Jesus, "My Lord and my God!" (John 20:28)."[13] There is no significant tendency among modern scholars to deny that either of these two verses identifies Jesus with God.[14]

Furthermore, the last Gospel elaborates on the role of Holy Spirit being sent as an advocate for believers.[13] The immediate context of these verses was providing "assurance of the presence and power of God both in the ministry of Jesus and the ongoing life of the community." Beyond this immediate context, these verses caused questions of relation between Father, Son and the Holy Spirit, their distinction and yet unity. These questions have been hotly debated over the following centuries, although mainstream Christianity has generally resolved the issue through the writing of creeds.[13]

Summarizing the role of Scripture in the formation of Trinitarian belief, Gregory Nazianzen argues in his Orations that the revelation was intentionally gradual:

The Old Testament proclaimed the Father openly, and the Son more obscurely. The New manifested the Son, and suggested the deity of the Spirit. Now the Spirit himself dwells among us, and supplies us with a clearer demonstration of himself. For it was not safe, when the Godhead of the Father was not yet acknowledged, plainly to proclaim the Son; nor when that of the Son was not yet received to burden us further.[15]

Scriptural texts cited as implying support

To support Trinitarianism, Bible exegetes cite references to the Trinity, to Jesus as God, and both to God alone and to Jesus as the Savior.

References to the Trinity

A few verses directly reference the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit:

- Matthew 3:16–17: "As soon as Jesus Christ was baptized, he went up out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and lighting on him. 17And a voice from heaven said, 'This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.' " (also Mark 1:10–11; Luke 3:22; John 1:32)

- Matthew 28:19: "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (see Trinitarian formula).

- 2 Corinthians 13:14: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with all of you."

- 1 John 5:7–8: "For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one." (This is the controversial Comma Johanneum, which did not appear in Greek texts before the sixteenth century.)

- Luke 1:35: "The angel answered and said to her, 'The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; and for that reason the holy Child shall be called the Son of God.' "

- Hebrews 9:14: "How much more, then, will the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself unblemished to God, cleanse our consciences from acts that lead to death, so that we may serve the living God!"

Jesus as God

Many verses in John, the epistles, and Revelation imply support for the doctrine that Jesus Christ is God and the closely related concept of the Trinity. The Gospel of John in particular supports Jesus' divinity. This is a partial list of supporting Bible verses:

- John 1:1 "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." together with John 1:14 "The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth." and John 1:18 "No one has ever seen God, but God the One and Only, who is at the Father's side, has made him known."[16]The Bible says "God the One and Only" in NIV.

- John 5:21 "For just as the Father raises the dead and gives them life, even so the Son gives life to whom he is pleased to give it."

- John 8:23–24: "But he continued,'You are from below; I am from above. You are of this world; I am not of this world. I told you that you would die in your sins; if you do not believe that I am [the one I claim to be], you will indeed die in your sins.'"

- John 8:58 "I tell you the truth," Jesus answered, "before Abraham was born, I am!"[17]

- John 10:30: "I and the Father are one."

- John 10:38: "But if I do it, even though you do not believe me, believe the miracles, that you may know and understand that the Father is in me, and I in the Father."

- John 12:41: "Isaiah said this because he saw Jesus' glory and spoke about him."—As the context shows, this implied the Tetragrammaton in Isaiah 6:10 refers to Jesus.

- John 20:28: "Thomas said to him, 'My Lord and my God!'"

- Philippians 2:5–8: "Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself and became obedient to death—even death on a cross!"

- Colossians 2:9: "For in Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form"

- Titus 2:13: "while we wait for the blessed hope—the glorious appearing of our great God and Saviour, Jesus Christ."

- 1 Timothy 3:16: "And without controversy great is the mystery of godliness: God was manifest in the flesh, justified in the Spirit, seen of angels, preached unto the Gentiles, believed on in the world, received up into glory."

- Hebrews 1:8: "But about the Son he [God] says, "Your throne, O God, will last for ever and ever, and righteousness will be the scepter of your kingdom."

- 1 John 5:20: "We know also that the Son of God has come and has given us understanding, so that we may know him who is true. And we are in him who is true—even in his Son Jesus Christ. He is the true God and eternal life."

- Revelation 1:17–18: "When I saw him, I fell at his feet as though dead. Then he placed his right hand on me and said: "Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and behold I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades." This is seen as significant when viewed with Isaiah 44:6: "This is what the LORD says—Israel's King and Redeemer, the LORD Almighty: I am the first and I am the last; apart from me there is no God."

The Bible also refers to Jesus as a man, which is in line with the Trinitarian concept that Jesus was fully human as well as fully divine which is expressed through the theological concept of kenosis.

God alone is the Savior and the Savior is Jesus

The Old Testament identifies the LORD as the only savior, and the New Testament identifies Jesus Christ as God and Savior. These verses are consistent with Trinitarianism, as well as various nontrinitarian beliefs (binitarianism, modalism, the Latter-Day Saints' godhead, Arianism, etc.).

- Isaiah 43:11: "'I, even I, am the LORD, and apart from me there is no savior.'"

- Titus 2:10: "and not to steal from them, but to show that they can be fully trusted, so that in every way they will make the teaching about God our Savior attractive."

- Titus 3:4: "But when the kindness and love of God our Savior appeared," in regard with:

- Luke 2:11: "'Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord.'"

- Titus 2:13: "while we wait for the blessed hope-the glorious appearing of our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ,"

- John 4:42: "They said to the woman, "We no longer believe just because of what you said; now we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this man [Jesus] really is the Savior of the world.'"

- Titus 3:6: "whom he poured out on us generously through Jesus Christ our Savior,"

History

The Origin of the Formula

The importance for the first Christians of their faith in God whom they called Father; in Jesus Christ whom they saw as the Son of God, the Word of God,[18] King, Saviour,[19] Master;[20] and in the Holy Spirit is expressed in formulas that link all three together, such as those in the Gospel according to Matthew, the Great Commission: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19); and in the Second Letter of St Paul to the Corinthians: "The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all."(2 Corinthians 13:14)

The doctrine of the divinity and personality of the Holy Spirit was developed by Athanasius in the last decades of his life.[21] In 325, the Council of Nicaea adopted a term for the relationship between the Son and the Father that from then on was seen as the hallmark of orthodoxy; it declared that the Son is "of the same substance" (ὁμοούσιος) as the Father. This was further developed into the formula "three persons, one substance." The answer to the question "What is God?" indicates the one-ness of the divine nature, while the answer to the question "Who is God?" indicates the three-ness of "Father, Son and Holy Spirit."

The Council of Nicaea was reluctant to adopt language not found in Scripture, and ultimately did so only after Arius showed how all strictly biblical language could also be interpreted to support his belief that there was a time when the Son did not exist. In adopting non-biblical language, the council's intent was to preserve what they thought the Church had always believed: that the Son is fully God, coeternal with God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

There is evidence indicating that one mediaeval Latin writer, while purporting to quote from the First Epistle of John, inserted a passage now known as the Comma Johanneum (1 John) which has often been cited as an explicit reference the Trinity. It may have begun as a marginal note quoting a homily of Cyprian that was inadvertently taken into the main body of the text by a copyist.[22] The Comma found its way into several later copies, and was eventually back-translated into Greek and included in the third edition of the Textus Receptus which formed the basis of the King James Version. Erasmus, the compiler of the Textus Receptus, noticed that the passage was not found in any of the Greek manuscripts at his disposal and refused to include it until presented with an example containing it, which he rightly suspected was concocted after the fact.[23] Isaac Newton, known mainly for his scientific and mathematical discoveries, noted that many ancient authorities failed to quote the Comma when it would have provided substantial support for their arguments, suggesting it was a later addition.[24] Modern textual criticism has since concurred with his findings; many modern translations now either omit the passage, or make it clear that it is not found in the early manuscripts.

Formulation of the Doctrine

The most significant developments in articulating the doctrine of the Trinity took place in the 4th century, with a group of men known as the Theologians.[25] Although the earliest Church Fathers had affirmed the teachings of the Apostles, their focus was on their pastoral duties to the Church under the persecution of the Roman Empire.[25] Thus the early Fathers were largely unable to compose doctrinal treatises and theological expositions. With the relaxing of the persecution of the church during the rise of Constantine, the stage was set for ecumenical dialogue.[25]

Trinitarians believe that the resultant councils and creeds did not discover or create doctrine, but rather, responding to serious heresies such as Arianism, articulated in the creeds the truths that the orthodox church had believed since the time of the apostles.[25]

The Trinitarian view has been affirmed as an article of faith by the Nicene (325/381) and Athanasian creeds (circa 500), which attempted to standardize belief in the face of disagreements on the subject. These creeds were formulated and ratified by the Church of the third and fourth centuries in reaction to heterodox theologies concerning the Trinity and/or Christ. The Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed, revised in 381 by the second of these councils, is professed by the Eastern Orthodox Church and, with one addition (Filioque clause), the Roman Catholic Church, and has been retained in some form in the Anglican Communion and most Protestant denominations.

The Nicene Creed, which is a classic formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity, uses "homoousios" (Greek: of the same essence) of the relation of the Son's relationship with the Father. This word differs from that used by non-Trinitarians of the time, "homoiousios" (Greek: of similar essence), by a single Greek letter, "one iota," a fact proverbially used to speak of deep divisions, especially in theology, expressed by seemingly small verbal differences.

One of the (probably three) Church councils that in 264–266 condemned Paul of Samosata for his Adoptionist theology also condemned the term "homoousios" in the sense he used it, with the result that, as the Catholic Encyclopedia article about him remarks, "The objectors to the Nicene doctrine in the fourth century made copious use of this disapproval of the Nicene word by a famous council." [26]

Moreover, the meanings of "ousia" and "hypostasis" overlapped at the time, so that the latter term for some meant essence and for others person. Athanasius of Alexandria (293–373) helped to clarify the terms.[27]

Because Christianity converts cultures from within, the doctrinal formulas as they have developed bear the marks of the ages through which the church has passed. The rhetorical tools of Greek philosophy, especially of Neoplatonism, are evident in the language adopted to explain the church's rejection of Arianism and Adoptionism on one hand (teaching that Christ is inferior to the Father, or even that he was merely human), and Docetism and Sabellianism on the other hand (teaching that Christ was identical to God the Father, or an illusion). Augustine of Hippo has been noted at the forefront of these formulations; and he contributed much to the speculative development of the doctrine of the Trinity as it is known today, in the West; the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory Nazianzus) are more prominent in the East. The imprint of Augustinianism is found, for example, in the western Athanasian Creed, which, although it bears the name and reproduces the views of the fourth century opponent of Arianism, was probably written much later.

These controversies were for most purposes settled at the Ecumenical councils, whose creeds affirm the doctrine of the Trinity.

According to the Athanasian Creed, each of these three divine Persons is said to be eternal, each almighty, none greater or less than another, each God, and yet together being but one God, So are we forbidden by the Catholic religion to say; There are three Gods or three Lords.—Athanasian Creed, line 20.

Modalists attempted to resolve the mystery of the Trinity by holding that the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost are merely modes, or roles, of God Almighty. This anti-Trinitarian view contends that the three "Persons" are not distinct Persons, but titles which describe how humanity has interacted with or had experiences with God. In the Role of The Father, God is the provider and creator of all. In the mode of The Son, man experiences God in the flesh, as a human, fully man and fully God. God manifests Himself as the Holy Spirit by his actions on Earth and within the lives of Christians. This view is known as Sabellianism, and was rejected as heresy by the Ecumenical Councils although it is still prevalent today among denominations known as "Oneness" and "Apostolic" Pentecostal Christians, the largest of these sects being the United Pentecostal Church. Trinitarianism insists that the Father, Son and Spirit simultaneously exist, each fully the same God.

The doctrine developed into its present form precisely through this kind of confrontation with alternatives; and the process of refinement continues in the same way. Even now, ecumenical dialogue between Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Roman Catholic, the Assyrian Church of the East, Anglican and Trinitarian Protestants, seeks an expression of Trinitarian and Christological doctrine which will overcome the extremely subtle differences that have largely contributed to dividing them into separate communities. The doctrine of the Trinity is therefore symbolic, somewhat paradoxically, of both division and unity.

Trinitarian Theology

Baptism as the beginning lesson

Baptism itself is generally conferred with the Trinitarian formula, "in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit" (Matthew 28:19); and Basil the Great (330–379) declared: "We are bound to be baptized in the terms we have received, and to profess faith in the terms in which we have been baptized." "This is the Faith of our baptism," the First Council of Constantinople declared (382), "that teaches us to believe in the Name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. According to this Faith there is one Godhead, Power, and Being of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit."

Matthew 28:19 may be taken to indicate that baptism was associated with this Trinitarian formula from the earliest decades of the Church's existence.[28] The formula is found in the Didache,[29] Ignatius,[30] Tertullian,[31] Hippolytus,[32] Cyprian,[33] and Gregory Thaumaturgus.[34] Though the formula has early attestation, the Acts of the Apostles only mentions believers being baptized "in the name of Jesus Christ" (Acts 2:38, 10:48) and "in the name of the Lord Jesus" (Acts 8:16, Acts 19:5). There are no Biblical references to baptism in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit outside of Matthew 28:19, nor references to baptism in the name of (the Lord) Jesus (Christ) outside the Acts of the Apostles.[35]

Commenting on Matthew 28:19, Gerhard Kittel states:

This threefold relation [of Father, Son and Spirit] soon found fixed expression in the triadic formulae in 2 C. 13:13, and in 1 Corinthians 12:4–6. The form is first found in the baptismal formula in Matthew 28:19; Did., 7. 1 and 3....[I]t is self-evident that Father, Son and Spirit are here linked in an indissoluble threefold relationship.[36]

In the synoptic Gospels the baptism of Jesus himself is often interpreted as a manifestation of all three Persons of the Trinity: "And when Jesus was baptized, he went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove, and alighting on him; and lo, a voice from heaven, saying, This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased." (Matthew 3:16–17)

One God

God is one, and the Godhead a single being: The Hebrew Scriptures lift this one article of faith above others, and surround it with stern warnings against departure from this central issue of faith, and of faithfulness to the covenant God had made with them. "Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD" (Deuteronomy 6:4) (the Shema), "Thou shalt have no other gods before me" (Deuteronomy 5:7) and, "Thus saith the LORD the King of Israel and his redeemer the LORD of hosts: I am the first and I am the last; and beside me there is no God." (Isaiah 44:6). Any formulation of an article of faith which does not insist that God is solitary, that divides worship between God and any other, or that imagines God coming into existence rather than being God eternally, is not capable of directing people toward the knowledge of God, according to the Trinitarian understanding of the Old Testament. The same insistence is found in the New Testament: "...there is none other God but one..." (1 Corinthians 8:4). The "other gods" warned against are therefore not understood as gods at all, but as substitutes for God, and so are, according to St. Paul, simply mythological (1 Corinthians 8:5).

Which brings the question, what is meant by "one?" In the Hebrew, the word for God is Elohim [אֱלֹהִים]. In every other instance where elohim is with a small e (indicating non-gods), it indicates a plurality because the word elohim is in fact plural. In the abovementioned passages, the Hebrew word for "one" is echad [אֶחָד] which may signify a compound unity, unified in perfect harmony and purpose, unlike the Hebrew word yachid which unequivocally means an absolute (not compound) singularity. The concept of echad would be similar to a perfectly functioning family or the cleaving of husband and wife as one flesh (cf. Genesis 2:24).

So, in the Trinitarian view, the common conception which thinks of the Father and Christ as two separate beings is viewed as incorrect by many but not all groups in Christianity and Messianicism. The central and crucial affirmation of Christian faith is that there is one savior, God, and one salvation, manifest in Jesus Christ, to which there is access only because of the Holy Spirit. The God of the Old is still the same as the God of the New. In Christianity, it is understood that statements about a solitary god are intended to distinguish the Hebraic understanding from the polytheistic view, which see divine power as shared by several beings, beings which can, and do, disagree and have conflicts with each other. The Gospel of John depicts the Father as united with Jesus as Jesus is united with his followers (John 17:20–23).

God exists in three persons

The "Shield of the Trinity" or "Scutum Fidei" diagram of traditional Western Christian symbolism.

This one God however exists in three persons, or in the Greek hypostases. God has but a single divine nature. Chalcedonians—Roman Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Anglicans and Protestants—hold that, in addition, the Second Persona of the Trinity—God the Son, Jesus—assumed human nature, so that he has two natures (and hence two wills), and is really and fully both true God and true human. In the Oriental Orthodox theology, the Chalcedonian formulation is rejected in favor of the position that the union of the two natures, though unconfused, births a third nature: redeemed humanity, the new creation.

In the Trinity, the Three are said to be co-equal and co-eternal, one in essence, nature, power, action, and will. However, as laid out in the Athanasian Creed, only the Father is unbegotten and non-proceeding. The Son is begotten from (or "generated by") the Father. The Spirit proceeds from the Father (or from the Father and through the Son—see filioque clause for the distinction). The Roman Catholic Church teaches that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

It has been stated that because God exists in three persons, God has always loved, and there has always existed perfectly harmonious communion between the three persons of the Trinity. One consequence of this teaching is that God could not have created Man in order to have someone to talk to or to love: God "already" enjoyed personal communion; being perfect, He did not create Man because of any lack or inadequacy He had. Another consequence, according to Rev. Fr. Thomas Hopko, an Eastern Orthodox theologian, is that if God were not a Trinity, He could not have loved prior to creating other beings on whom to bestow his love. Thus we find God saying in Genesis 1:26-27, "Let us make man in our image, in our likeness, and let them rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, over all the earth, and over all the creatures that move along the ground. So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them." For Trinitarians, emphasis in Genesis 1:26 is on the plurality in the Deity, and in 1:27 on the unity of the divine Essence. A possible interpretation of Genesis 1:26 is that God's relationships in the Trinity are mirrored in man by the ideal relationship between husband and wife, two persons becoming one flesh, as described in Eve's creation later in the next chapter. Genesis 2:22 Some Trinitarian Christians support their position with the Comma Johanneum described above, even though it is widely regarded as inauthentic and was not used patristically.

Mutually indwelling

A useful explanation of the relationship of the distinct divine persons is called "perichoresis," from Greek going around, envelopment (written with a long O, omega—some mistakenly associate it with the Greek word for dance, which however is spelled with a short O, omicron). This concept refers for its basis to John 14–17, where Jesus is instructing the disciples concerning the meaning of his departure. His going to the Father, he says, is for their sake; so that he might come to them when the "other comforter" is given to them. At that time, he says, his disciples will dwell in him, as he dwells in the Father, and the Father dwells in him, and the Father will dwell in them. This is so, according to the theory of perichoresis, because the persons of the Trinity "reciprocally contain one another, so that one permanently envelopes and is permanently enveloped by, the other whom he yet envelopes." (Hilary of Poitiers, Concerning the Trinity 3:1). [4]

This co-indwelling may also be helpful in illustrating the Trinitarian conception of salvation. The first doctrinal benefit is that it effectively excludes the idea that God has parts. Trinitarians affirm that God is a simple, not an aggregate, being. The second doctrinal benefit is that it harmonizes well with the doctrine that the Christian's union with the Son in his humanity brings him into union with one who contains in himself, in St. Paul's words, "all the fullness of deity" and not a part. (See also: Theosis). Perichoresis provides an intuitive figure of what this might mean. The Son, the eternal Word, is from all eternity the dwelling place of God; he is, himself, the "Father's house," just as the Son dwells in the Father and the Spirit; so that, when the Spirit is "given," then it happens as Jesus said, "I will not leave you as orphans; for I will come to you" (John 14:18)

Some forms of human union are considered to be not identical but analogous to the Trinitarian concept, as found for example in Jesus' words about marriage: "For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother, and cleave to his wife; And they twain shall be one flesh: so then they are no more twain, but one flesh" (Mark 10:7–8). According to the words of Jesus, married persons are in some sense no longer two, but joined into one. Therefore, Orthodox theologians also see the marriage relationship as an image, or "ikon" of the Trinity, relationships of communion in which, in the words of St. Paul, participants are "members one of another." As with marriage, the unity of the church with Christ is similarly considered in some sense analogous to the unity of the Trinity, following the prayer of Jesus to the Father, for the church, that "they may be one, even as we are one." John 17:22

Eternal generation and procession

Trinitarianism affirms that the Son is "begotten" (or "generated") of the Father and that the Spirit "proceeds" from the Father, but the Father is "neither begotten nor proceeds." The argument over whether the Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, or from the Father and the Son, was one of the catalysts of the Great Schism, in this case concerning the Western addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed.

This language is often considered difficult because, if used regarding humans or other created things, it would necessarily imply time and change; when used here, no beginning, change in being, or process within time is intended and is in fact excluded. The Son is generated ("born" or "begotten"), and the Spirit proceeds, eternally. Augustine of Hippo explains, "Thy years are one day, and Thy day is not daily, but today; because Thy today yields not to tomorrow, for neither does it follow yesterday. Thy today is eternity; therefore Thou begat the Co-eternal, to whom Thou saidst, 'This day have I begotten Thee." {Psalm 2:7}

Son begotten, not created

Because the Son is begotten, not made, the substance of his persona is that of Yahweh, of deity. The creation is brought into being through the Son, but the Son Himself is not part of it except through His incarnation.

The church fathers used a number of analogies to express this thought. St. Irenaeus of Lyons was the final major theologian of the second century. He writes "the Father is God, and the Son is God, for whatever is begotten of God is God."

Extending the analogy, it might be said, similarly, that whatever is generated (procreated) of humans is human. Thus, given that humanity is, in the words of the Bible, "created in the image and likeness of God," an analogy can be drawn between the Divine Essence and human nature, between the Divine Persons and human persons. However, given the fall, this analogy is far from perfect, even though, like the Divine Persons, human persons are characterized by being "loci of relationship." For Trinitarian Christians, this analogy is particularly important with regard to the Church, which St. Paul calls "the body of Christ" and whose members are, because they are "members of Christ," also "members one of another."

However, any attempt to explain the mystery to some extent must break down, and has limited usefulness, being designed, not so much to fully explain the Trinity, but to point to the experience of communion with the Triune God within the Church as the Body of Christ. The difference between those who believe in the Trinity and those who do not, is not an issue of understanding the mystery. Rather, the difference is primarily one of belief concerning the personal identity of Christ. It is a difference in conception of the salvation connected with Christ that drives all reactions, either favorable or unfavorable, to the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. As it is, the doctrine of the Trinity is directly tied up with Christology.

Economic and Ontological Trinity

- Economic Trinity: This refers to the acts of the triune God with respect to the creation, history, salvation, the formation of the Church, the daily lives of believers, etc. and describes how the Trinity operates within history in terms of the roles or functions performed by each of the Persons of the Trinity—God's relationship with creation.

- Ontological (or essential or immanent) Trinity: This speaks of the interior life of the Trinity "within itself" (John 1:1–2, note John 1:1)—the reciprocal relationships of Father, Son and Spirit to each other.

Or more simply—the ontological Trinity (who God is) and the economic Trinity (what God does). Most Christians believe the economic reflects and reveals the ontological. Catholic theologian Karl Rahner went so far as to say "The 'economic' Trinity is the 'immanent' Trinity, and vice versa."[37]

The members of the Trinity are equal ontologically, but not necessarily economically. In other words, the Trinity is not symmetrical in terms of function, or in relationship to one another. The roles of each differ both among themselves, and in relationship to creation. Furthermore, the Trinity is not symmetrical with regards to origin. The Son is begotten of the Father (John 3:16). The Spirit proceeds from the Father (John 15:26). Only the Father is neither begotten nor proceeding (See Athanasian Creed), but is alone "unoriginate" and eternally communicates the Divine Being to the Word, the Son, by "generation" and to the Spirit by "spiration," in that the Spirit "proceeds from the Father" and in the words of some {Eastern} theologians, "rests on the Son" as seen in the baptism of Jesus.

Economical subordination is implied by the genitive of terms like "Father of," "Son of," and "Spirit of." While orthodox Trinitarianism rejects ontological subordination, it affirms that the Father, being the source of all that is, created and uncreated, has a monarchical relation to the Son and the Spirit. Or, in other terms, it is from the Father that the mission of the Breath and Word originate: whatever God does, it is the Father that does it, and always through the Son, by the Spirit. The Father is seen as the "source" or "fountainhead" from which the Son is born and the Spirit proceeds, much as one might observe water bubbling out of a spring without worrying about when it began doing so. However, this language is hemmed in with qualifications so severe that the analogy in view is easily lost, and is a source of perpetual controversy. The main points, however, are that "there is one God because there is one Father" and that, while the Son and Spirit both derive their existence from the Father, the communion between the Three, being a relationship of Divine Love, is such that there is no subordination according to substance. As one transcendent Being, the Three are perfectly united in love, consciousness, will, and operation. Thus, it is possible to speak of the Trinity as a "hierarchy-in-equality."

This concept is considered to be of momentous practical importance to the Christian life because, again, it points to the nature of the Christian's reconciliation with God. The excruciatingly fine distinctions can issue in grand differences of emphasis in worship, teaching, and government, as large as the difference between East and West, which for centuries have been considered practically insurmountable.

Western Theologian Catherine Mowry LaCugna finds common ground with Eastern scholarship through rejecting modern individualist notions of personhood and emphasising the self-communication of God. Following on from Rahner, she says that God is known ontologically only through God's self-revelation in the economy of salvation, and that "Theories about what God is apart from God's self-communication in salvation history remain unverifiable and ultimately untheological."[38] She says faithful Trinitarian theology must be practical and include an understanding of our own personhood in relationship with God and each other—"Living God's life with one another."[39]

The terminology of Godhead concerns the nature of God and so is largely distinct from that which concerns specifically the interrelations of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Old Testament evidence

Old Testament theophanies

In the Old Testament, several theophanies are recorded in which "God appeared" to one or more human beings in a physical manifestation that could be seen and heard.

- Genesis 12:7,18:1 — God appeared to Abraham

- Genesis 26:2,24 — God appeared to Isaac

- Genesis 35:1,9,48:3 — God appeared to Jacob

- Exodus 3:16,4:5 — God appeared to Moses

- Exodus 6:3 — God appeared to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob

- Leviticus 9:4,16:2 — God appeared to Aaron

- Deuteronomy 31:15 — God appeared to Moses and Joshua

- 1Samuel 3:21 — God appeared to Samuel

- 1Kings 3:5,9:2,11:9 — God appeared to Solomon

- 2Chronicles 1 — God appeared to David

- 2Chronicles 7:12 — God appeared to Solomon

The Angel (Messenger) of the Lord

- Genesis 16:7–14

- Genesis 22:9–14

- Exodus 3:2

- Exodus 23:20,21

- Numbers 22:21–35

- Judges 2:1–5

- Judges 6:11–22

- Judges 13:3

God identified as "the Father" in the Old Testament

- Deuteronomy 32:6 (Moses' time)

- Isaiah 63:15,64:8 (pre-exile)

- Malachi 2:10 (post-exile)

God identified as "the Son" in the Old Testament

- Psalm 2:12 includes the phrase "kiss his Son."

- The "Anointed One" in verse 2 is called the "Son" in verse 12.

- Both Jewish and Christian scholars say this Psalm speaks of the Messiah.

- God's works are applied to "the Son" (compare Psalm 24:1–2; Job 34:24; Jeremiah 51:19–23)

- The "Son" is begotten (compare 2Samuel 7:14; Acts 13:33)

- Proverbs 30:4 includes the phrase "His son's name."

- Two separate persons are spoken of: "His name" and "His son's name"

- This cannot be a metaphor or impersonal force.

- This is not Hebrew parallelism.

- Isaiah 9:6 includes the phrase "a son is given," along with the following phrases:

- "Wonderful Counselor" (compare Judges 13:17-18)

- "born to us" (compare Isaiah 7:14, "God with us")

- "Mighty God" (compare Isaiah 10:21)

- "Eternal Father"

- "Prince of Peace" (compare Psalm 2:7–9)

God the Spirit in the Old Testament

- 1Samuel 10:10,19:20,23

- 2Samuel 23:1

- 1Kings 22:24

- Nehemiah 9:30

- Psalms 51:11

- Isaiah 63:10,11

- Micah 2:7

Deity of the Holy Spirit in the Old Testament:

Words of the Holy Spirit called the words of God:

Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Protestant distinctions

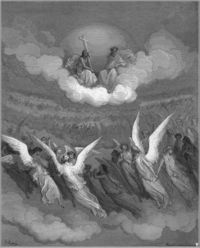

The Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev, using the theme of the "Hospitality of Abraham." The three angels symbolize the Trinity.

The Western (Roman Catholic) tradition is more prone to make positive statements concerning the relationship of persons in the Trinity. It should be noted that explanations of the Trinity are not the same thing as the doctrine itself; nevertheless the Augustinian West is inclined to think in philosophical terms concerning the rationality of God's being, and is prone on this basis to be more open than the East to seek philosophical formulations which make the doctrine more intelligible.

The Christian East, for its part, correlates ecclesiology and Trinitarian doctrine, and seeks to understand the doctrine of the Trinity via the experience of the Church, which it understands to be "an ikon of the Trinity" and therefore, when St. Paul writes concerning Christians that all are "members one of another," Eastern Christians in turn understand this as also applying to the Divine Persons.

The principal disagreement between Western and Eastern Christianity on the Trinity has been the relationship of the Holy Spirit with the other two hypostases. The original credal formulation of the Council of Constantinople was that the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father." While this phrase is still used unaltered in the Eastern Churches, it became customary in parts of the Western Church, beginning with the provincial Third Council of Toledo in 589, to add the clause "and the Son" (Latin filioque) into the Creed. Although this was explicitly rejected by Pope Leo III, it was finally used in a Papal Mass by Pope Benedict VIII in 1014, thus becoming official throughout the Roman Catholic Church. The Eastern Churches object to it on both ecclesiological and theological grounds.

Anglicans have made a commitment in their Lambeth Conference, to provide for the use of the creed without the filioque clause in future revisions of their liturgies, in deference to the issues of Conciliar authority raised by the Orthodox.

Most Protestant groups that use the creed also include the filioque clause. However, the issue is usually not controversial among them because their conception is often less exact than is discussed above (exceptions being the Presbyterian Westminster Confession 2:3, the London Baptist Confession 2:3, and the Lutheran Augsburg Confession 1:1–6, which specifically address those issues). The clause is often understood by Protestants to mean that the Spirit is sent from the Father, by the Son, a conception which is not controversial in either Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. A representative view of Protestant Trinitarian theology is more difficult to provide, given the diverse and decentralized nature of the various Protestant churches.

Naming the Persons

Some feminist theologians refer to the persons of the Holy Trinity with gender-neutral language, such as "Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer (or Sanctifier)." This is a recent formulation, which seeks to redefine the Trinity in terms of three roles in salvation or relationships with us, not eternal identities or relationships with each other. Since, however, each of the three divine persons participates in the acts of creation, redemption, and sustaining, traditionalist Christians reject this formulation as suggesting a new variety of Modalism. Some theologians prefer the alternate terminology of "Source, and Word, and Holy Spirit."

Responding to feminist concerns, orthodox theology has noted the following: a) the names "Father" and "Son" are clearly analogical, since all Trinitarians would agree that God is beyond all gender; b) that, in translating the Creed, for example, "born" and "begotten" are equally valid translations of the Greek word "gennao," which refers to the eternal generation of the Son by the Father: hence, one may refer to God "the Father who gives birth"; this is further supported by patristic writings which compare the "birth" of the Divine Word "before all ages" (i.e., eternally) from the Father with his birth in time from the Virgin Mary; c) Using "Son" to refer to the Second Divine Person is most proper only when referring to the Incarnate Word, Jesus, who is clearly male; d) in Semitic languages, such as Hebrew and Aramaic, the noun translated "spirit" is grammatically feminine. Images of God's Spirit in Scripture are also often feminine, as with the Spirit "brooding" over the primordial chaos in Genesis 1, or grammatically feminine, such as a dove.

Logical Coherency

On the face of it, the doctrine of the Trinity seems to be logically incoherent as it appears to imply that identity is not transitive—"for the Father is identical with God, the Son is identical with God, and the Father is not identical with the Son." Recently, there have been two philosophical attempts to defend the logical coherency of Trinity, one by Richard Swinburne and the other by Peter Geach et al. The formulation suggested by the former philosopher is free from logical incoherency, but it is debatable whether this formulation is consistent with historical orthodoxy. Regarding the formulation suggested by the latter philosopher, not all philosophers would agree with its logical coherency. Richard Swinburne has suggested that "the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit be thought of as numerically distinct Gods." Peter Geach suggested that "a coherent statement of the doctrine is possible on the assumption that identity is 'always relative to a sortal term."[40] Christians admit that the Trinity is beyond our finite understanding to understand completely, as God is beyond our finite understanding.

On the other hand, some Messianic groups, the Branch Davidian Seventh Day Adventists, and even some scholars within (but not necessarily representing) denominations such as Southern Baptist Convention view the Trinity as being comparable to the concept of a family, hence the familial terms of Father, Son, and the implied role of Mother for the Holy Spirit. The Hebrew word for "God," Elohim, which has an inherent plurality, has the function as a surname as in "Yahweh Elohim." The seeming contradiction of Elohim being "one" is solved by the fact that the Hebrew word for "one" is "echad " meaning compound unity, harmonious in direction and purpose; not "yachid" which means singularity.

Ambivalence to Trinitarian doctrine

Some Protestant Christians, particularly some members of the restoration movement, are ambivalent about the doctrine of the Trinity. While not specifically rejecting Trinitarianism or presenting an alternative doctrine of the Godhead and God's relationship with humanity, they are neither dogmatic about the Trinity nor hold it as a test of true Christian faith. Some, like the Society of Friends (Quakers) and Christian Unitarians, may reject all doctrinal or creedal tests of true faith. Others, like some members of the restorationist Churches of Christ, in keeping with a distinctive understanding of "Scripture alone," say that since the doctrine of the Trinity is not clearly articulated in the Bible, it cannot be required for salvation. Still others may look to church tradition and say that there has always been a Christian tradition that faithfully followed Jesus without such a doctrine.

Unorthodox Trinitarianism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) identify the Trinity (or Godhead) as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, but they regard these three as one in purpose and unity, but not in identity.

The Trinity in Christian Science is found in the unity of God, the Christ, and the Holy Ghost or—"God the Father-Mother; Christ the spiritual idea of sonship; divine Science or the Holy Comforter." The same in essence, the Trinity indicates "the intelligent relation of God to man and the universe." [41]

Nontrinitarianism

Some Christian traditions either reject the doctrine of the Trinity, or consider it unimportant. Persons and groups espousing this position generally do not refer to themselves as "Nontrinitarians." They can vary in both their reasons for rejecting traditional teaching on the Trinity, and in the way they describe God.

Criticism and defense

Following is an outline of basic objections raised by critics of the Trinity and a theologian's defense of each:[42]

- The word Trinity is not found in the Bible. Response: This has no bearing on whether or not the Bible teaches the doctrine. The word "monotheism" is not in the Bible yet the concept is clearly taught in scripture.

- There is no verse in the Bible that teaches the Trinity. Response: Various verses teach that the Father is called God Phil. 1:2, the Son is called God (John 1:1,14, and the Holy Spirit is called God (Acts 5:3-4). There are verses that suggest the Trinity since they mention all three together: Matt. 3:16-17. Matt. 28:19, 2 Cor.13:14

- The Trinity is three separate Gods. Response: The Trinity doctrine, by definition, is monotheistic. The Shema of the Old Testament (Deut. 6:4) is seen in the New Testament ("The Lord our God is one." Mark 12:29). The New Testament knows God as Father, as Son, and as Holy Spirit.

- Three gods cannot be one God. Response: The Trinity is not three gods. The Trinity is one God in three persons.

- Three persons cannot be one person. Response: The Doctrine of the Trinity does not state that God is one person. The Trinity is one God in three persons.

- The Trinity is illogical. Response: There is no logical reason why the Trinity cannot be a possibility. An analogy would be time which is past, present, and future. Another example is a woman can be wife to her husband, daughter to her parents, mother to her children, sister to her siblings.

- The Trinity is a pagan idea. Response: Other religions have included triads (three separate gods) in their theology. The Trinity is one God. There are many verses in the OT that contain plural references to the one God: 1) 1:1-26; NIV Job 33:4; 2) Gen. 17:1; Gen. 18:1; {{Bibleref2|Ex. 6:2-3; 24:9-11; 33:20; {{Bibleref2|Num. 12:6-8; {{Bibleref2|Psalm 104:30; 3) Gen. 19:24 with {{Bibleref2|Amos|4:10-11; {{Bibleref2|Is.48:16} Furthermore, mere similarity in appearance between two beliefs does not dictate that one belief came from the other.

- Jesus cannot be God because He did not know all things, slept, grew in wisdom, said the Father is greater than I, etc. Response: This objection fails to take into consideration the Hypostatic Union which states that Jesus had two natures: divine and human. As a man, Jesus cooperated with the limitations of His humanity. Jesus would sleep, grow in wisdom, and say the Father was greater than He. These do not negate that Jesus was divine since they reference His humanity and not His divinity.

- Jesus cannot be God because this would mean that God died and God can't die. Response: Jesus' sacrifice was divine, as well as human, in nature. Jesus died. But, we know that God cannot die. So, if the divine nature did not die, how can it be said that Jesus' sacrifice was divine in nature? The answer is that the attributes of divinity, as well as humanity, were ascribed to the person Jesus. Therefore, since the person of Jesus died, His death was of infinite value because the properties of divinity were ascribed to the person in His death. This is called the Communicatio Idiomatum.

Nontrinitarian groups

Since Trinitarianism is central to so much of church doctrine, nontrinitarians have mostly been groups that existed before the Nicene Creed was codified in 325 or are groups that developed after the Reformation, when many church doctrines came into question[43]

In the early centuries of Christian history adoptionists, Arians, Ebionites, Gnostics, Marcionites, and others held nontrinitarian beliefs. The Nicene Creed raised the issue of the relationship between Jesus' divine and human natures. Monophysitism ("one nature") and monothelitism ("one will") were heretical attempts to explain this relationship. During more than a thousand years of Trinitarian orthodoxy, formal nontrinitarianism, i.e., a doctrine held by a church, group, or movement, was rare, but it did appear. For example, among the Cathars of the 13th century. The Protestant Reformation of the 1500s also brought tradition into question. At first, nontrinitarians were executed (such as Servetus), or forced to keep their beliefs secret (such as Isaac Newton). The eventual establishment of religious freedom, however, allowed nontrinitarians to more easily preach their beliefs, and the 19th century saw the establishment of several nontrinitarian groups in North America and elsewhere. These include Christadelphians, Jehovah's Witnesses, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Unitarians. Twentieth-century nontrinitarian movements include Iglesia ni Cristo and the Unification Church. Nontrinitarian groups differ from one another in their views of Jesus Christ, depicting him variously as a divine being second only to God the Father (e.g., Jehovah's Witnesses), Yahweh of the Old Testament in human form, God (but not eternally God), Son of God but inferior to the Father (versus co-equal), prophet, or simply a holy man.

Of notable exception are Oneness Pentecostals, who affirm that God came to Earth as man (i.e., manifested Himself) in the man Jesus Christ. Oneness Pentecostals fully affirm, like Trinitarians, that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man. One can understand Oneness Pentecostals by replacing the Trinitarian term 'person' with the term 'mode' or 'manifestation' when discussing the Christian Godhead. Many Oneness Pentecostals can recite the first Nicene Creed, as it rejects Arianism, yet preserves the oneness of God and divinity of Jesus Christ.

In popular culture

Trinity is the central female character in the movies, Matrix trilogy. Some believe that the three main characters resemble the Holy Trinity throughout the trilogy. Morpheus as the Father, Neo as the Son, and Trinity as the Holy Spirit. Another view is that Morpheus represents Elijah, or John the Baptist as the one who sought out and recognized that Neo had the dedication to constantly seek truth. It was Morpheus who baptized Neo and announced to the others that Neo was the One. While none of them are certain of what God is, they are certain that what they previously knew to be the truth, was indeed a lie to prevent discovery of the truth that they were being used as energy to fuel their own selfish fantasies while keeping all the Agent Smiths "on the payroll" (see Trinity (The Matrix)).

Linda Evangelista, Naomi Campbell, and Christy Turlington, were called the "Trinity" of top supermodels in the 1990s.[citation needed]

In the Valérian comics, The Rage of Hypsis and In Uncertain Times, the Trinity appeared as Harry Quinlan, the character played by Orson Welles in the 1958 film Touch of Evil, (Father); a hippie (Son) and a broken jukebox (Holy Spirit).

The Irish comedian Dave Allen irreverently satirised the Trinity as Big Daddy (Father), The Kid (Son) and Spook (Holy Spirit).[citation needed]

In the book Angela's Ashes there is a scene where Frank McCourt, as a child, mistakenly refers to the "Father, the Son, and the Holy Toast."

In the Fritz Lang film Metropolis, the city mayor Joh Fredersen represents the Father and the humble city proletariat as the Holy Spirit. The son of the mayor, Freder Fredersen, represents the Son. The film ends in statement: The intermediator between brain [Father] and hands [Holy Spirit] is Heart (Son).

Also, in Postcolonial Theory, "The Holy Trinity" is a term coined by Professor Robert J.C. Young, a well-known postcolonial critic currently based at NYU, with regards to the three main postcolonial theorists whose work constitutes much of the debate in this thriving and controversial field of study: Edward Said, Homi K Bhabha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.[44]

Notes

- ^ Liddell & Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon', entry for Τριάς, retrieved December 19, 2006

- ^ McGrath, Alister E. Understanding the Trinity. Zondervan, 9789 ISBN 0310296811

- ^ Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, II.XV (retrieved on December 19, 2006).

- ^ W.Fulton in the "Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics"

- ^ [1] History of the Doctrine of the Trinity. Accessed September 15, 2007.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Religion," Vol. 14, p.9360, on Trinity

- ^ (cf. Gregory Nazianzen, 'Or. theol., v, 26; Epiphanius, Ancor. 73, Haer. 74; Basil, Adv. Eunom. II, 22; Cyril Alex., In Joan., xii, 20.)

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia "Trinity", Old Testament

- ^ (Epiph., "Haer.," viii, 5; Cyril Alex., "Con. Julian.," I)

- ^ ("Haer.," Ixxiv)

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia: "the doctrine is not explicitly taught in the New Testament"

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Britannica, Trinity

- ^ a b c d e The Oxford Companion of the Bible, Trinity

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, The Anchor Bible: The Gospel According to John (XIII-XXI), pp. 1026, 1032

- ^ Gregory Nazianzen, Orations, 31.26

- ^ Textual critic Bart D. Ehrman asserts that the original text of John 1:18 referred to Jesus as "unique Son," not "God the One and Only." See Misquoting Jesus, 2005. The "unique Son" reading is found in the textus receptus and in some modern Bible translations.

- ^ The Trinitarian interpretation of this statement is that Jesus is claiming for himself the name of God, Yahweh, which is translated as "I am" (see Exodus 3:14

- ^ Gospel of John

- ^ Martyrdom of Polycarp

- ^ First Apology of Justin Martyr

- ^ On Athanasius, Oxford Classical Dictionary, Edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. Third edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- ^ Wallace, Daniel B. "The Comma Johanneum and Cyprian," accessed online 16 February 2006.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2d ed. Oxford University'," 1968 p.101

- ^ An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture

- ^ a b c d Bingham, Jeffrey, "HT200 Class Notes," Dallas Theological Seminary, (2004).

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ Some groups, such as Oneness Pentecostals, demur from the Trinitarian view on baptism. For them, the fact that Acts does not use the formula outweighs all other considerations, and is a liturgical guide for their own practice. For this reason, they often focus on the baptisms in Acts, citing many authoritative theological works. For example, Kittel is cited where he is speaking of the phrase "in the name" (Greek: εἰς τὸ ὄνομα) as used in the baptisms recorded in Acts:

The distinctive feature of Christian baptism is that it is administered in Christ (εἰς Χριστόν), or in the name of Christ (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα Χριστοῦ). (Gerhard Kittel, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1977), 1:539.)

The formula (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα) seems rather to have been a tech. term in Hellenistic commerce ("to the account"). In both cases the use of the phrase is understandable, since the account bears the name of the one who owns it, and in baptism the name of Christ is pronounced, invoked and confessed by the one who baptises or the one baptised (Acts 22:16) or both. (Kittel, 1:540.)

Those who place great emphasis on the baptisms in Acts often likewise question the authenticity of Matthew 28:19 in its present form. A. Ploughman, apparently following F. C. Conybeare, has questioned the authenticity of Matthew 28:19, however, the majority of scholars of New Testament textual criticism accept the authenticity of the passage. There are no variant manuscripts regarding the formula, and the extant form of the passage is attested in the Didache and other patristic works of the first and second centuries;[citation needed] for most textual critical scholars this is sufficient evidence to prove authenticity.

- ^ 7:1, 3 online

- ^ Epistle to the Philippians, 2:13 online

- ^ On Baptism 8:6 online, Against Praxeas, 26:2online

- ^ Against Noetus, 1:14 online

- ^ Seventh Council of Carthage online

- ^ A Sectional Confession of Faith, 13:2online

- ^ Baptism "in the name of" need not necessarily be taken as referring to a formula used in the ceremony in either Matthew or Acts; it may merely indicate the establishment of a relationship, corresponding to the phrases "baptized into Christ Jesus" (Romans 6:3) and "baptized into Christ" (Galatians 3:27). Compare "baptized ... into John's baptism" (Acts 19:3), "baptized in the name of Paul" (1 Corinthians 1:13), "baptized into Moses" (1 Corinthians 10:2).

- ^ Kittel, 3:108.

- ^ K Rahner, The Trinity (Herder & Herder:1970) p22

- ^ Catherine Mowry LaCugna, God For Us (Harper Colins:1973) p231

- ^ Catherine Mowry LaCugna, God For Us (Harper Colins:1973) p410

- ^ Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Online, on Trinity, Link

- ^ Eddy, Mary Baker; Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures

- ^ Slick, Matt. "The Trinity, the Hypostatic Union, and the Communicatio Idiomatum," Christian Apologetics and Research Ministry, 2007. http://www.carm.org/doctrine/3.htm Accessed 09-15-2007

- ^ See indulgences, particular judgment, primacy of the Pope, purgatory, transubstantiation, etc.

- ^ (Young, Robert J.C., Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race London: Routledge, 1994, p.163)

See also

- God

- Jesus

- Christ

- God the Father

- Arianism

- Fleur de lys

- Godhead

- Holy Trinity Icon

- Nontrinitarianism

- Oneness Pentecostal

- Social Trinity

- Trikaya

- Trimurti, the Hindu Trinity

- Trinitarian Universalism

- Tritheism

- Unitarianism

Wikimedia Commons has media related to:

- Ahura, the Zoroastrian Trinity

- Ayyavazhi Trinity

- Holy Trinity columns